This is part eight of the review. For the previous parts click here.

As last year, West put a major focus on fielding. To help with this, we continued our analysis of fielding through the Fielding Impact (FI) stat.

FI is a number that tries to analyse how many runs a team saves (or loses) through the three main skills: catching, stopping and throwing down the stumps. It is certainly not perfect as it works on averages and qualitative judgement, but it does allow us to compare effectiveness of fielding at both team and player level. Here are runs saved per game:

The first game of the season is at the top, and the average FI is the pink line. Wins are in maroon (naturally) and losses are in blue.

A few things stand out.

There is no correlation between winning and runs saved or lost.

There was also a great variation in fielding over the season (from 39 saved to 37 lost). Despite a good middle of the season, the start and end were poor. This is a trend we also saw last season.

Overall fielding may appear to have declined from last year – where West finished in the positive – however, these team stats also include half chances and harsher judgements on fielding standards than last year, meaning players are going for more catches and stops than last season. This is a positive, although it would be even better if more of those chances were executed successfully.

At a team level, we can break this down to all specific areas of improvement.

Catches

The biggest impact is catching. Taking an “expected” catch saves, on average, 6.73 runs, but dropping one costs 15.71. The old maxim of “catches win matches” is better described as “drops reduce your chance of winning”, but that doesn’t roll off the tongue quite as well.

At club level you expect about 30% of catches to be dropped. If you catch 75% you are at a very high level. This figure doesn’t include catches where you only have half a chance or need a stroke of brilliance to pull off.

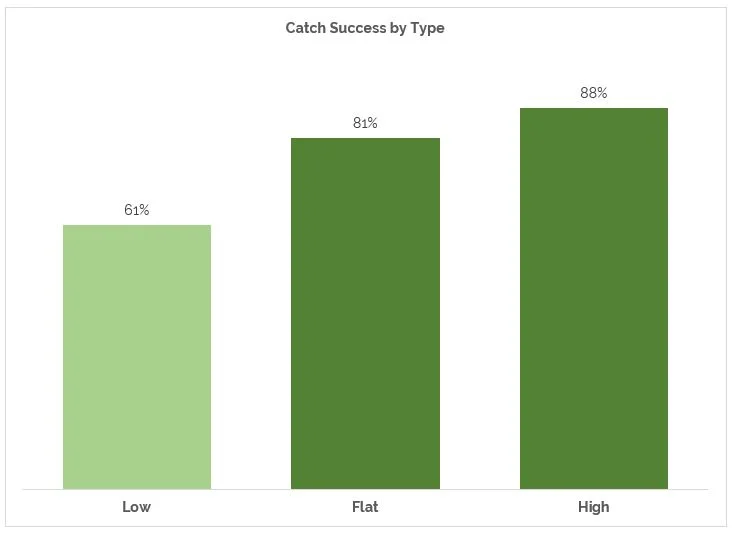

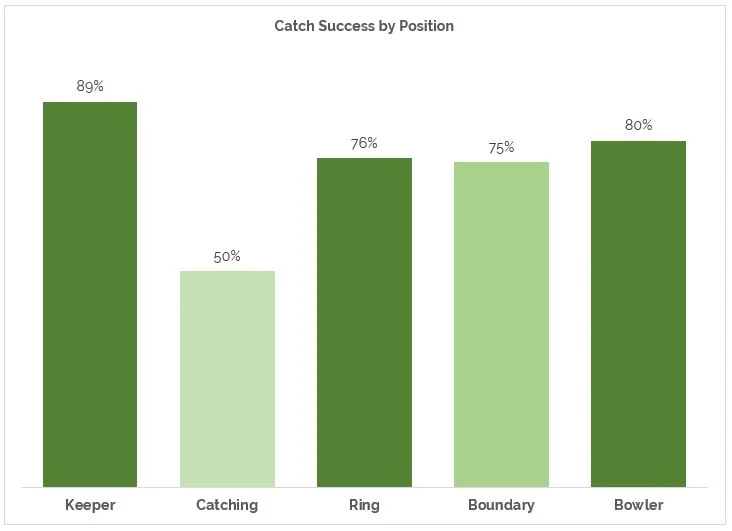

West had 73 expected chances – remember we are excluding half chances - in Premier cricket, holding 75%. This likely puts West near the top of catching for the league (although without figures it’s hard to judge). Broken down further this looks like:

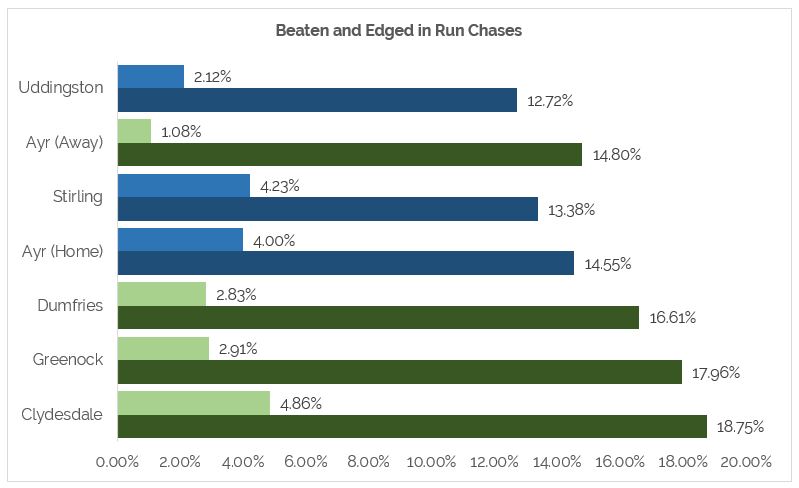

We can see top-class performance in both high and flat catches. Also, as expected, the keeper held most chances. Caught and bowled was successful but only had five chances all season. Ring and boundary catching was excellent.

Low catches had the most chances – 28 – and 11 drops making it the worst type of catch. Most of this was in close catching. 12 chances went here and six were dropped (five drops were from 11 low chances).

Drilling down, we can see the fast bowlers only had 44% of chances held by the slips. This dropped to 20% (one catch from five chances) in overs 11-20.

From this evidence, it’s recommended West look to maintain standards on most catching types but put in as much time as possible on low catch, especially at slip with the fast bowlers in the first half of the innings.

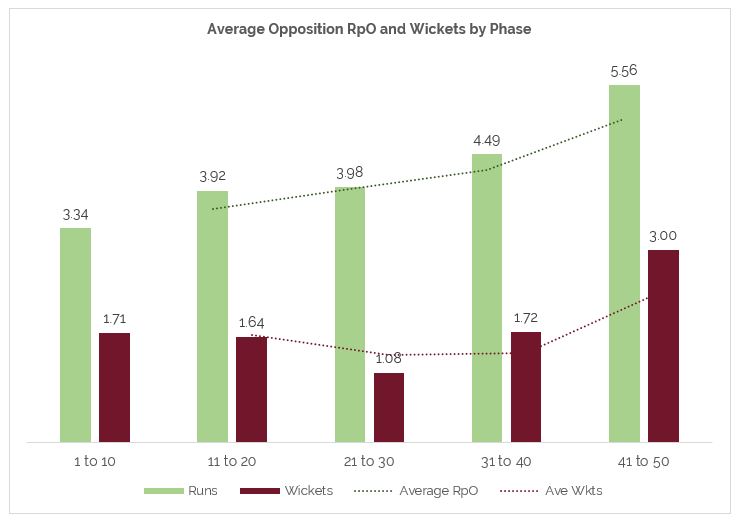

Ground fielding

Saving runs is also difficult to measure. We know – on average – a single piece of excellent fielding will save 2.06 runs. A misfield costs the same. Here is the breakdown of runs saved and given away:

From this graphic you can see positional performance. The ring fielders dominated, saving a balance of over 40 runs over the season (59.68 lost, 100.85 saved). The pack of bubbles in the top left shows you little difference between positions other than number of chances. Every position was comfortable in the black. West’s ground work is on point.

The next step in development is going for more balls by developing a mindset to push harder to get to more balls.

Throwing

The final skill is throwing for run outs. This is another hard skill to measure because a throw at the stumps that misses might not have resulted in a run out anyway. If it was a clearly out miss with all three stumps to aim at, the cost was 5.61 runs. A direct hit that resulted in a run out with one stump to aim at saved 16.83 runs.

West had 45 throws at the stumps all season. 12 hit at a 27% success rate. This is below what you expect at club level, but “expected hit” throws were at 50%, which is about average.

Three (25%) of these direct hits resulted in a run out, showing how hard it is to complete due to the influence of the batsman’s judgement and speed, and the umpire’s decision making. It also shows how important it is to get as many throws off as reasonable.

Additionally, there are throws that result in a run out from a “take and break”, where the keeper or bowler executes the run out. This was counted as saving 5.61 runs. There were 10 of these.

So, in trying to account for all these factors, we can say West lost 129 runs from missed run outs but made back 62 runs from completed run outs (direct hits, or take and breaks).

The balance was -32.

This may appear slightly harsh because in club cricket we tend to see a run out as a bonus. Missing a throw is not as “bad” as dropping a catch. However, the fact remains a missed throw is still a lost opportunity for a wicket and will cost extra runs: The batsman could have been out, but he remained in and continued to score. Remember, we are trying to establish how much effect fielding has on the opposition’s final score.

Team fielding performance overall

Returning to overall team performance then, we can combine these numbers.

West finished on -31 in Premier Division cricket, which is an average of -2.21 per game.

Two runs is certainly not enough to influence the outcome of an average match. In fact, some of the worst fielding performances did not lead to a loss. For example, West had a -37 score against Dumfries and -35 against Ayr and won both. You can certainly “get away” with poor fielding as a team.

On the other hand, the best fielding performance of the year was a loss against Clydesdale, demonstrating that West’s fielding kept them in the game when they could have lost more easily. Also. the last over loss against Poloc was a +3 for fielding. There were opportunities to make FI higher which were not taken. Had FI been higher, West would likely have won as it was such a close match.

The bottom line is team fielding alone rarely influences the outcome of the game, but it can keep you in a match longer, which gives you a better chance of success. It is also much more important in close games, where it is more likely to make the difference between winning and losing.