In part four of this review of the club cricket season, we look at how the team bowled overall.

Bowlers are less troubled by game situation than batsmen because they have the same goal most of the time: Concede as few runs as possible and take wickets. Dots and W’s are universally useful.

Let’s see how West did overall:

Even in these days of detailed analysis, the humble Bowling Average (BoA) and Strike Rate (SR) are still powerful indicators of good bowling. In the WDCU Premier Division, a BoA below 20.00 puts you in the top bracket, and below 17.50 puts you in the top 10 (best was 13.38). Top SR is in the 19.00-30.00 range.

As the green indicators show, three bowlers achieved a competent BoA and two SR. The spinners outperformed the seamers by this measure, which is reflective of the league overall where five of the top six wicket takers were spinners.

One way of comparing bowler’s performance without the influence of conditions and opposition strength is by Strike Rate Ratio (SRR). An SRR of 1.0 is the exact average strike rate for the team. The higher above the worse you bowl, the lower the better. This means we can also compare strike rates over the last three seasons. Here are all the bowlers with over 200 deliveries between 2016-18:

Players in italics are no longer playing as they are overseas players. As you can see, Lowtop is the best wicket-taker over the last three seasons by this measure. You can also see the below-par wickets of both Winter and Kodak.

Speaking of wickets, there were four types of dismissal (minus one stumping and five run outs) with most wickets falling to catches, as you would expect. However, with almost 45% of wickets falling to bowled or LBW, it’s clear West attack the stumps, especially Winter.

The seamer was the best example of the above. He took 59% of wickets this way (more LBWs than anyone else despite his protests). Alongside the one wicket he had caught by the keeper or slips all season, you can see how he is effectively a stump to stump bowler. Comparably, Quicksky got 28% of his wickets by attacking the stumps but had eight of his 13 catches taken at slip or by the keeper.

The main spinners also seemed to have complimentary styles. Lowtop had more bowled and LBW (he also got the one stumping), Northflood had more caught, most often through mis-timed drives and pulls caught in the ring (six out of nine outfield catches).

Chances and false shots

Going together with actual wickets is the chances a bowler creates. Not every edge goes to hand, not every miss-hit is caught. The more opportunities for a wicket, the better the bowling.

The bowler with the most wickets also had the greatest number of dropped catches. The ratio stays about the same for all the top bowlers. Winter may consider his 63% catches unlucky and Lowtop might be happy to see fielders held the ball 78% of the time from his bowling. But that is only a difference of one drop all season.

Not every piece of bowling skill ends in a chance though. Let’s also look at false shots; play and miss, edges and shots where the batsman was not in control.

With the average opposition side playing a false shot 27% of the time (26% for West) the stand out bowler at drawing a bad shot is Kodak. He was the only bowler to “win the ball” more than 200 times with a 31% rate. However, just to show that winning the ball does not guarantee wickets, even though Kodak induced far more false shots, the conversion was one of the lowest, needing more than 11 bad shots before he got a wicket. Northflood was the reverse, converting his lower number of false shots into wickets almost twice as often. This could be because Kodak beat the bat a lot more than Northflood.

Speaking of beating the bat, we can also see a possible reason why the leg spin of Bridge was unsuccessful in 2018 (dropped after six matches). His bowling did not produce many false shots, and he was least likely to get a wicket with one. He beat the bat more but found the edge less. Of all the poor shots played to his bowling, 63% did not find the edge (compared to 48% for the other two spinners) and 5% did (compared to 13%). In short, this analysis concludes he was turning the ball past the edge without threating either the stumps – for bowled and LBW – or the edge of the bat for keeper catches (zero chances all season).

Phase performance

Moving on, performance at different stages of the innings offers an insight into strong and weak spots in the attack.

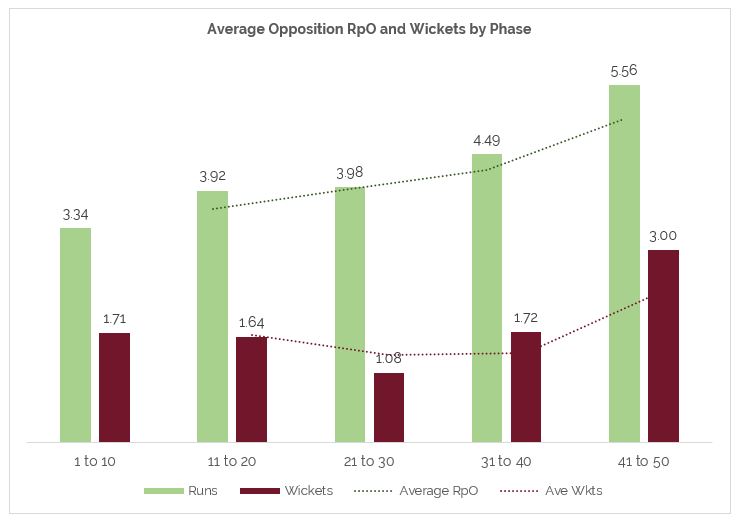

The trend line for runs is similar to West’s batting; a gradual acceleration. Wickets fall evenly through the innings, with most falling at the back end.

There is a sign of problem in the middle overs where average wickets dips to 1.08. On the plus side, the opposition rarely did well at the death, keeping the average RpO below six.

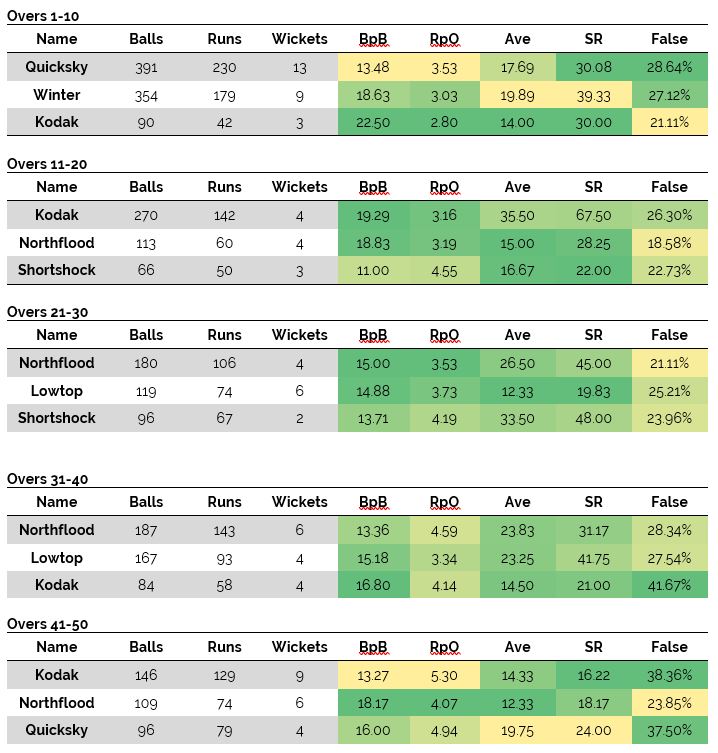

Top performers in each phase (minimum of 10 overs bowled) were:

The colour scale goes from green (best) to yellow (worst). You can quickly see who did best in each category at each phase:

Opening: Quicksky, Kodak

Early Middle: Lowtop, Northflood, Shortshock

Late Middle: Lowtop, Kodak

Death: Kodak, Northflood, Quicksky

McCallum also bowled effectively but does not appear here because he only bowled 22 overs all season.

You can also see strike rates go up in the middle overs, and with a quick comparison we can see why:

The spinners maintain a reasonable if slightly high SR, topping at 38. The seamers, after an effective start, saw the SR go up past 100 before getting it back under control in the last 20 overs.

The faster bowlers rarely had good wicket-taking form in the early middle overs.

One solution to this is to find better seamers for that phase, but the number of false shots did not change much either, suggesting the batsmen were not dominating, merely getting out less often. Despite a similar level of false shots, there were fewer chances and more drops in these overs.

The lowest catch percentage was in overs 11-20 and there were zero chances in the following 10 overs. This suggests drops in the first 20 overs ended up costing West in the next 10. It also explains why paceman strike rates are so high: A severely weakened key dismissal. Perhaps the solution for the seamers is to try and hit the stumps more and rely on catching less in the middle overs.

Runs conceded

As we have touched on runs conceded, let’s go into more detail.

Attacking shots yield faster scoring at higher cost. The classic example is the pull shot, with the highest strike rate and RpO, but a relatively low average and Balls per Wicket (BpW).

Rotation shots like glances and pushes have a high average and are where the batsman is most in control but slow the scoring rate. You would imagine defensive shot to be the safest, and that is certainly true of the leave. However, the block is most often played when the batsman gets a good ball, meaning he often gets out to it. On the other hand, the leave is by far safest.

This means the best approach is to try to get the batsman to play pure defence as much as possible by attacking the stumps. The risk is opening the glance and flick through the leg side. So, attacking off stump is safest.

This is not news. However, there is a secondary tactic that is possibly underused: fast short pitched bowling. This is based on two things: the effectiveness of West’s bouncers and the high risk of the pull shot. The bouncer was bowled 28 times by West – in only seven games – and took three wickets for 11 runs (two boundaries). That’s a great performance. Roughly half were attacked by the batsman but even counting just these balls, the average was 11.00. Meanwhile, the pull shot – played to short, straight balls mostly – averaged 24.60 (five wickets for the seamers).

The conclusion here is the bouncer can be used more, if the bowler is confident of getting the ball above the waist (if the ball does not bounce above the waist it can be worked off the hip at 90.25 against seam).

When wickets are hard to come by in overs 11-30 IS a good time to consider a wicket falls every nine bouncers bowled.

Going back to defensive shots, the block is a rough indicator of how well a bowler is bowling. While not always the case, it is true that a good ball is mostly met by an attempted block by the batsman. The more attempted blocks the better the bowler’s accuracy.

Kodak forced the most defensive shots, but spoiled the party with a high number of wides. The next three bowlers kept defensive shots high and wides low. This is did correlate to RpO with all three having average to excellent rates.

It seems once defensive shots drop and wides go up, so does RpO as Bridge and Shortshock dipped below 27% with a higher number of wides. Both had a redline RpO (over five). Quicksky is the outlier, looking very much like a typical wild strike bowler. He took 18 wickets at 24, but had fewest defensive shots played and bowled most wides. As a bowler who prides himself on accuracy, Quicksky certainly has work to do in the off season to get back to his best.

Returning to RpO; the measure is a good general indicator of performance for bowlers to keep the rate down. Here are the West bowlers “run saving” stats:

Winter is the stand-out dry bowler here, with top scores in every category. Kodak is not far behind in comparison. Northflood stands close by, which is excellent for a spinner who bowled almost 20% of his overs at the death. Below the redline are three bowlers who failed to impress, although Shortshock will feel slightly unlucky as he bowled as many dots per over as Quicksky but went for more runs per over.

We can also get an idea of the number of bad balls a bowler is serving up by looking at Balls per Boundary (BpB). The higher the BpB, the fewer bad balls a bowler delivers. However, this stat also includes good balls that go for a boundary, such as edging the ball down to third man. A more accurate measure is the number of boundaries scored with the batsman in control of the shot. This is BpCB (Balls per Controlled Boundary).

Winter and Kodak lead the way in overall BpB. They bowl fewer four balls than any other bowler. These two also see a big jump in deliveries when you remove boundaries from poor shots. Winter sees an extra 3.34 added. The other bowlers who benefit are McCallum (5.66) and Quicksky (2.59). These bowlers bowl fewer bad balls that go for a boundary, but it looks worse than it is because more of their good balls hit the rope.

Northflood is the spinner who goes for the least boundaries. He is also one the bowlers to benefit the least from BpCB (1.34) meaning not many of his good balls go for a boundary. The other spinners have a similar story, but clearly bowled more bad balls that were put away (especially Bridge with a BpCB of 10.46, the third worst of all bowlers).

The most important conclusion from all this is to bowl as many good balls as possible.

This is not rocket science of course, but by attempting to remove the influence of fortune on bowling performance we can get a truer picture on how bowlers will achieve this.

For example, Winter is far and away the most accurate bowler in the team (most balls defended, most dots, least number of boundaries), and is about average for beating the batsman yet took wickets slower than almost any other bowler. His off-season preparation needs to focus on either becoming more of a containing bowler with the old ball or developing a new way to take wickets.

Another example is Lowtop, who tends to buy wickets more often: His run-saving numbers are all about average for West (which is slightly below average for the league). However, he has the good habit of having the chances he creates taken more often. The has led to the best BoA and SR in the team, and an especially strong performance in the middle overs. When defending a total, he has been expensive but also takes wickets. His role is a strike bowler. The development opportunity for him is to learn how to bowl more defensively when needed, or to look to ways of generating even more chances for wickets (in case his luck ever runs out).

In the next article, we move on to bowling performance in the first innings, as part of an analysis of the team’s ability to chase a target.