This is part six of the review of the Premier Division season for West of Scotland. This article looks into the chasing skills of the side.

West were great at setting up the game with the ball, but that’s only half the job. How did West do with the bat?

Tactically, the main difference is knowing what you are chasing. You can alter your approach based on the score. For example, you can feel safe batting more slowly chasing a score with a high Win%. Whereas, necessity insists you bat faster when chasing an above par score. Three an over is plenty chasing 100 but will quickly put you behind the rate chasing 300.

We can judge how difficult a chase is by Win%, and by this measure, West won a single game against the odds but lost two games from a winning position. The other matches went to form.

We can get a sense of how these games went by looking at the margin of victory.

This graphic shows how West did in won chases. The closer to the top right of the chart, the easier the win, the closer to the bottom left, the closer the game.

The size of the bubble represents the chance of victory at half time. You can see here West had comfortable wins against Clydesdale and Ayr, and closer ones against Greenock (where time was not an issue, but wickets fallen was) and Dumfries.

How was this done? Each chase is different, so let’s pick one specific example. The match against Ayr looks like the most confident performance: Winning by six wickets with balls to spare despite the halftime Win% at 48%. Here is the change in Win% over West’s innings:

As you can see, after a solid start three wickets (the dots on the chart) fell between over 10-18.

This caused a slowing of the run rate and a dip to 27%. This was a key moment. The West batsmen took about 30 balls to stabilise, then accelerated significantly up to the 32 over mark, peaking at 77% after 32 overs when a wicket fell.

The new partnership, after a dip, gradually pushed the % back up. In the last 20 balls of the match, the RpO jumped quickly and West won with balls to spare: A well-managed chase, featuring a chunk of the game where there was a significant risk of failure.

You can see clearly here how dynamically managing the chase depending on the situation is far more relevant than average scores.

To compare, let’s see a game that was lost.

Chasing a slightly below par score, West took the Win% get to its highest point at 61% after 10 overs. There was a 100+ partnership, but the pair left the Win% the same as when they got together. Remember, against Ayr a much smaller run partnership had added over 30% and made the final run-in much easier.

From here, there was a collapse with three wickets falling in a short time and the Win% dropping, as expected. At 34% with only 100 balls left, there was precious little time to consolidate, and wickets tumbled to defeat.

While the collapse of nine wickets for 67 runs is an obvious failing of the middle order, it could be argued the big stand made the collapse more likely because there was less margin for error. In this way the stand of 80 in the Ayr match put West in a stronger position than the stand of 112 in the Uddingston match.

This comparison does bring up an important question: How late can you leave a push for victory? Against Ayr, there were more wickets early on, and the Win% dropped much further. However, an attacking recovery made the difference. Against Uddingston, a push did not come despite a bigger stand. Of course, the batsmen were not to know a collapse was going to happen in the latter case. Yet, with hindsight, would a higher Win% at 30 overs have given the team the same increased sense of security even during a flurry of wickets? We can only guess based on limited evidence, but it certainly seems logical to assume an earlier push is more effective.

The leads into the psychology of a chase. Of course, we can’t measure how either anxiety or over-confidence influences a chance of victory, However, we can get close by using Win% as a measure. In the Uddingston example, it’s possible to imagine a scenario where the batsmen building a big stand were so comfortable with “ticking over” around 50% they did not account for the potential of a collapse. You can also imagine a sudden drop in Win% can steel a pair to counter-attack as they are aware they need to improve the rate.

One interesting game from this lens is the loss to Ayr.

West were at 98% chance of victory at 145-2 chasing 181. Then four top order wickets fell for one run, and another six runs later. Five wickets in 17 balls is an extraordinary loss of wickets. Even from this point, the Win% was high with just 2.38 an over needed, but with seven wickets down, the tail did not wag.

Could the mindset of losing quick wickets been to worry about another collapse and therefore cause it?

The only clue is in how the wickets fell.

Three catches behind the wicket from three chances suggests good bowling and fielding was at the root of it. There was also 44% of balls beating the bat (including the catches) during these four overs, highlighting that Ayr certainly had more luck regardless of whether this was via bowling skill or batting nerves. Certainly, only one attacking shot (a pull) was played in this phase, suggesting there were not many terrible balls to attack. However, we can’t be sure as no batsman had much time to define a tactical approach.

If it was great bowling, there is little one can do. However, if it was batting nerves, one suggestion is to counter-attack more quickly after a couple of wickets. This carries more risk, but also gives a psychological boost when it works(as it has for West is 2018).

All we can do in analysis is highlight these points and ask batsmen to be mindful in the moment of making decisions that they feel will give the best chance of success.

The truth about false shots in the chase

Picking up on playing and missing, this element adds to the feeling of winning or losing a game.

A game where the ball is beating the bat regularly feels like you are losing. However, looking at the stats we can see this is not true:

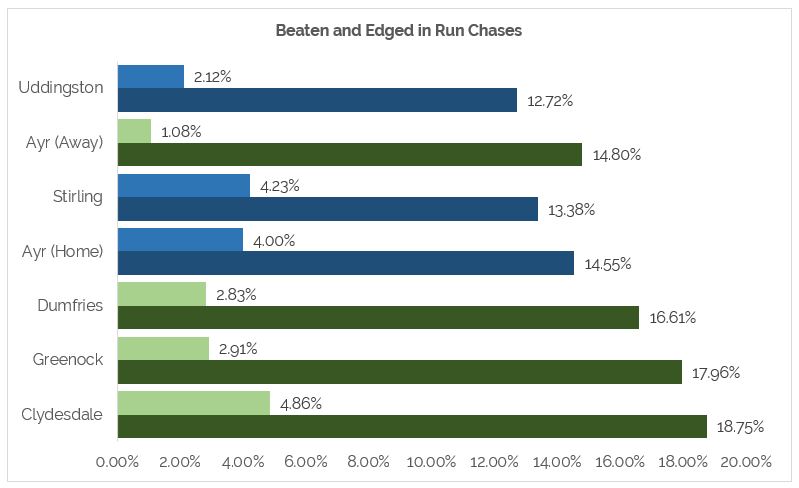

You can see the games lost in blue are also the games with the fewest edges or ball beating the bat. The games won – in green - saw more balls beating the bat. There is no correlation in run chases between result and how much you play and miss (or edge) the ball.

This shows players they should have nothing to fear from the ball beating the bat, as long as wickets do not fall.

Overall, we can see chasing was a strength of West in 2018, with some notable exceptions. West have shown chases can be managed as a team, even under pressure. That said, the lessons from the collapses are to develop a more assertive, flexible tactical approach that gives a robust ability to manage any situation, no matter how dire.

The next part will take a more general look at the batting, including how West played spin, dismissal types and shot averages.