This is part five of the review of the Premier Division season for West of Scotland. This article examines how the team did bowling first in 50 over games.

Historically, batting second has been less effective in league cricket. In 2018, the trend switched to a fifty-fifty split and West swapped totally to being far more successful chasing.

When bowling first, West’s average target to chase was 193; slightly lower than the average league score of 197. When chasing, West reached an average of 170, with a smaller variation in scores than batting first. (214-118). Games that were chased successful averaged 6.25 wickets down in 263 balls (44 overs). Lost games were an average of 59 runs short, all out in 233 balls (39 overs). Another indicator that West’s batting tends to follow the average of large margins.

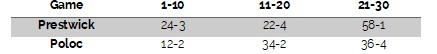

It is perhaps a sign of bowling strength that West only had one above par score to chase, especially in a season of high scores across the league. Here are those games:

As you can see there are no correlations between result and the main indicators of bowling success. This would make sense, as the bowlers set the game up, but the batsmen still must do their job.

There is one correlation; Win%: This figure is worked out by the difference between the par score at the ground and the actual score. It’s indicates where a team is at half time. In almost every game won, the opposition scored at least 20 below par making the win% between 72-80%. Only one game in this group was lost. It is certainly a testament to West’s bowling first plan that five opponents from seven did not get to par, and the average Win% was 60.33%.

You can argue, then, that West’s bowling set up most games, only once allowing an opponent to get away with an above par score. The spinners were not quite as effective as the seamers, suggesting seam can be used more in the first innings.

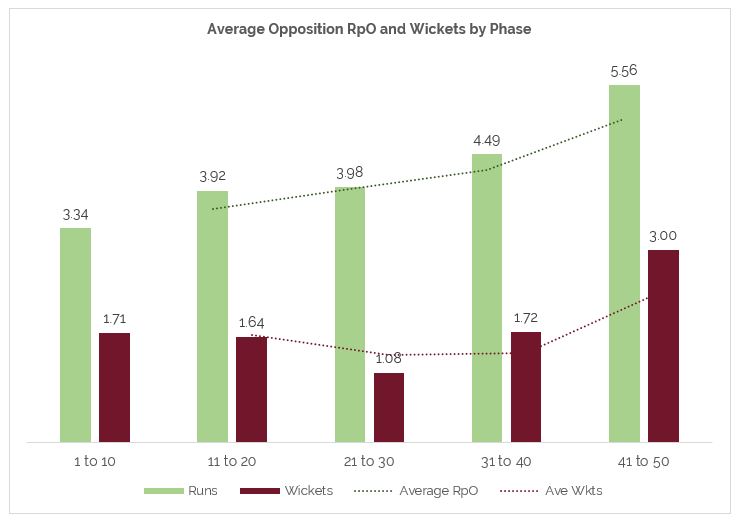

Of course, this analysis only looks at runs because the only measure of success is keeping runs to a minimum. However, this ignores the impact of wickets during the first innings. Wickets do the following things:

Slow the run rate.

Increase the chances of a side being bowled out before 300 balls are bowled.

So, while wickets are certainly important, they are also hard to work out their value. What’s better? figures of 0-30 or 4-50? Pure Win% would say the 0-30, but if the wickets lead to a side being bowled out, 4-50 is better. It’s very dependent on how the whole team does.

What this means is when bowling first, you have two chances to succeed; keep the opposition below par with tight bowling and bowl the opposition out. The former has a stronger correlation to wins in West games.

You can, of course, focus on both. A series of dots will increase the chances of a wicket. However, often you must choose between containing or attacking. In these moments, knowing West’s best chances of success come through containment (bowling first) is a key factor to understand.

How did West do on the wicket-taking element? The bowlers took wickets at a useful rate bowling first. The average for the league is 7.38 wickets per game. West averaged 9.29. 10 wickets were taken 57% of the time, better than the league overall at 44%.

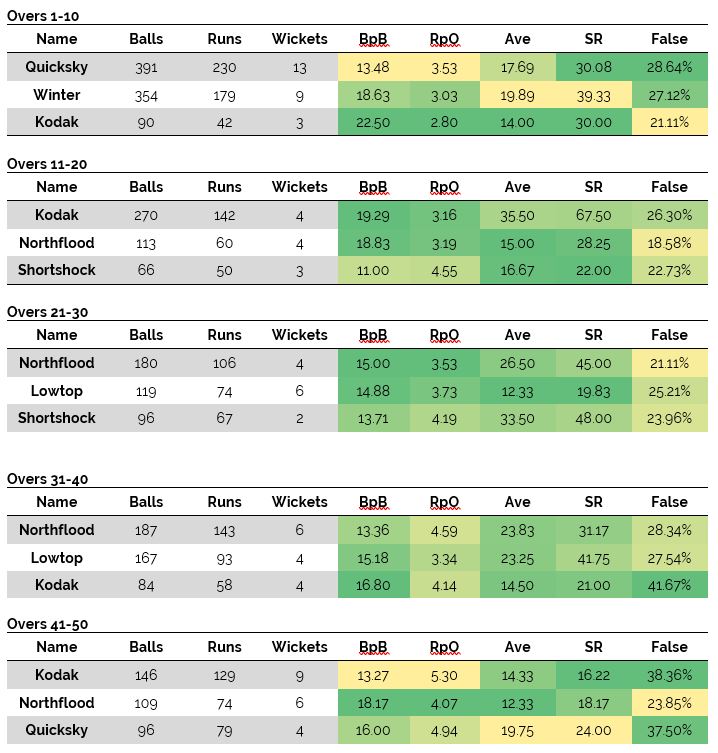

Here are the averages for bowling first:

Overall BoA is kept low thanks to Northflood, Kodak and Winter. Quicksky will be slightly disappointed to not take double figure wickets, especially as he beat the bat more than average. Lowtop was noticeably less of a threat in the first innings than the second. A development point for Lowtop is to work his first innings plans, be that dot bowling or wicket taking, where he has been solid but not as destructive in either discipline.

SR is better bowling first than second, mainly thanks to Northflood, Kodak and Winter. Winter was a totally different bowler between the two, looking like a superstar when bowling first, and a dot ball specialist when bowling second (the opposite of Lowtop).

It tells a tale that those with the best wicket-taking skills are mostly those with the best Win%+. There is clearly a link, but it’s not crucial. Bowlers can take this knowledge and develop themselves, knowing how best to use the skills they have, and gain some new ones over the winter.

Following on from this, we will look at batting second to see how well the batsmen paired with the bowlers.